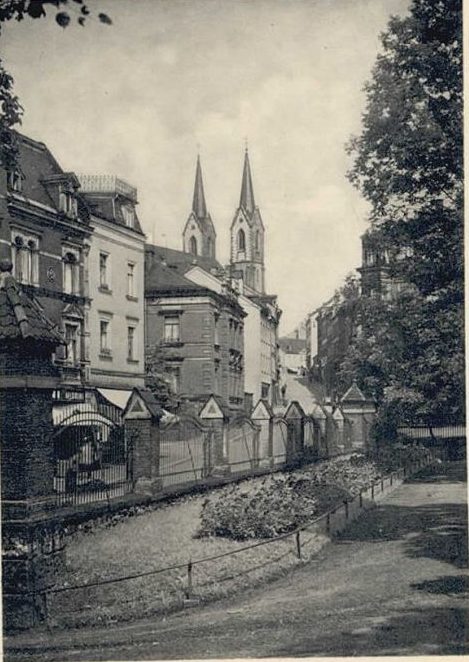

Max Heymann’s life in Hof began with the acquisition of the shoe shop “Ludwig Schloß” in Lorenzstraße 7 on 21st October 1912, where he held the position of as first chairman of the “Vereinigung der Schuhwarenhändler in Hof und Umgebung” (Association of Shoe Merchants in Hof and the Surroundings) for several years; in the 1920s he was a member of the Hof welfare committee. According to a statement by Hans Högn, Lord Mayor of Hof from 1950 to 1970, Max Heymann was a very friendly and helpful man whose business suffered already early from the hostilities of the National Socialists. They used slogans in front of the shop window like: “Don’t buy from the Jews” or “Jews are our misfortune”. On Saturdays, even SA people stood at the shop door and bullied customers who wanted to enter the shop. In 1933 his business declined economically and Max Heymann filed for bankruptcy. In December 1934 the Heymann family had to close the shoe repair business, in January 1936 also the shoe trade was finally closed. Fortunately for him, he and his family got “the bread of mercy of a synagogue servant” and so they moved into the attic apartment of the synagogue building in Hallstraße 9 on December 1st, 1937. The year before, on December 23rd, 1936, Max’s son Siegfried Heymann had emigrated to New York with less than $50. During the Reichspogromnacht the synagogue in Hof was destroyed and the Heymann family was arrested after the demolition of their home furnishings. Later they moved to a so-called “Judenhaus” (“house for Jews”) in Mannheim. The sister of Max’s wife Ella, Elisabeth Stern, her husband Wilhelm Stern and their daughter Lore Stern also lived in this house. The Wagner-Bürckel-campaign, which took place from 22nd to 23rd October 1940, was the precursor of the mass deportations to the East. The aim of the action carried out by Heinrich Himmler was to deport Jews from Southwestern Germany to Southern France, with the exception of citizens who were very ill or living in mixed marriages. However, the government there was opposed to the transports, which were contrary to international law, which is why no further transports to the south of France took place after the protest. The approximately 6,500 Jews were transported to the Gurs (Dép.Pyrénées-Atlantiques) internment camp in Southern France, which also affected Max, Ella and their son Walter Heymann. The situation there was very bad, as there was too little water and hunger was a constant companion. As a consequence these circumstances favoured the spread of diseases such as typhoid fever and dysentery, which led to the death of about 800 prisoners in the winter of 1940/41. Further camps were set up to which the jewish prisoners were distributed. On 29th November 1942 Max Heymann died at the age of 60 in the internment camp Nexon (Dép. Haute-Vienne). His son Walter was later transported to the camp Les Milles, where the prisoners were beaten and kicked for bad work, which often led to death. Due to great pressure from the German government on France, the extermination of Jews was also made possible there. The central collection and internment camp, whose organisation and structure corresponded to that of other concentration camps, was Drancy. On 22nd June 1942, 65,000 Jews were transported to Auschwitz or Sobibor, which is why Walter Heymann died in Auschwitz on 21st December 1943. His mother Ella Heymann and other Jews were liberated by Allies in the Masseube (dép. Gers) camp. She emigrated to the USA to see her son Siegfried again after 10 years and to live with him.

Source: Hübschmann 2019, p. 175 – 188