The story of the Franken family

Holidays in Buenos Aires.

Who wouldn’t want that?

Max Franken would probably have liked to forego his unvoluntary trip to Argentina.

Max Franken was born on 25th March 1881 in Emmerich (Rhine) as the youngest son of his parents Joseph David Franken and Minna Franken, born Strauß. He had six half brothers and one sister. Joseph David Franken was a coppersmith and master plumber. He often told his children about his war own experiences in the battles at Sedan, Le Mans etc. Some of his brothers later learnt a trade such as tailoring or shoemaking. Max Franken became a merchant. In the First World War two of Max Franken’s brothers fell.

Max Franken met his later wife Therese Silberberg in Halle where he had recently become the owner of the men’s clothing store “Eduard Cohn”. Therese Silberberg was the third of six children of Leopold Silberberg, who was also a merchant, and Henriette Jütel Silberberg. Max Franken and Therese Silberberg got married on 8th June 1910. They continued to live in Halle for a while, later they moved to Plauen and from there finally to Hof. There they had three daughters: Margarete, Lore and Käthe.

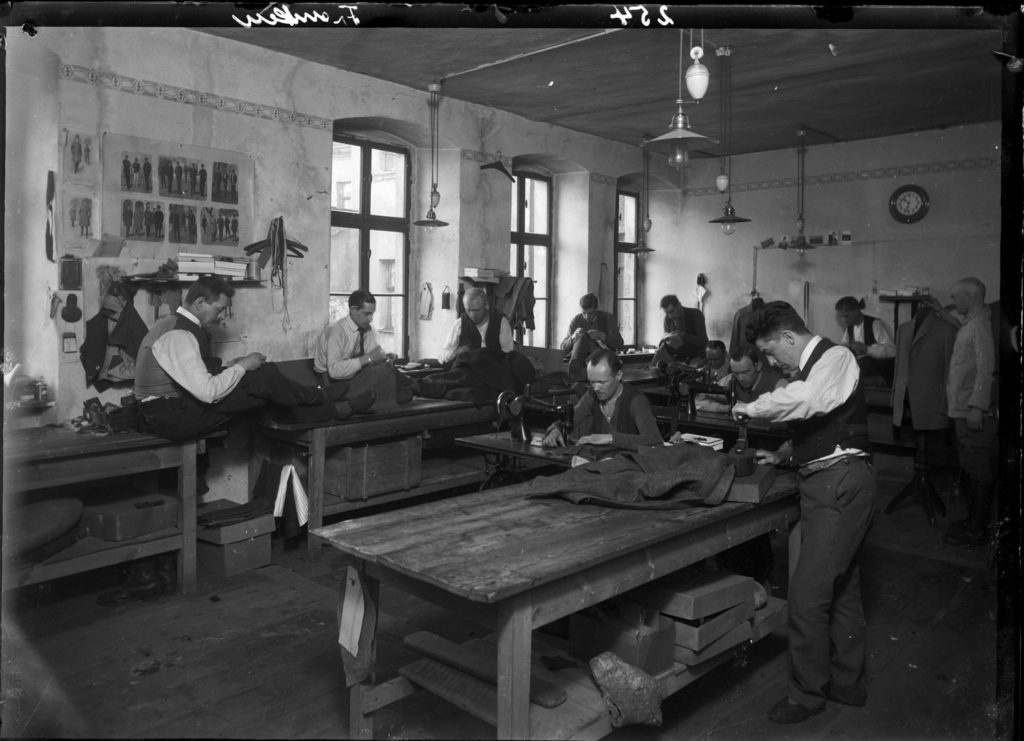

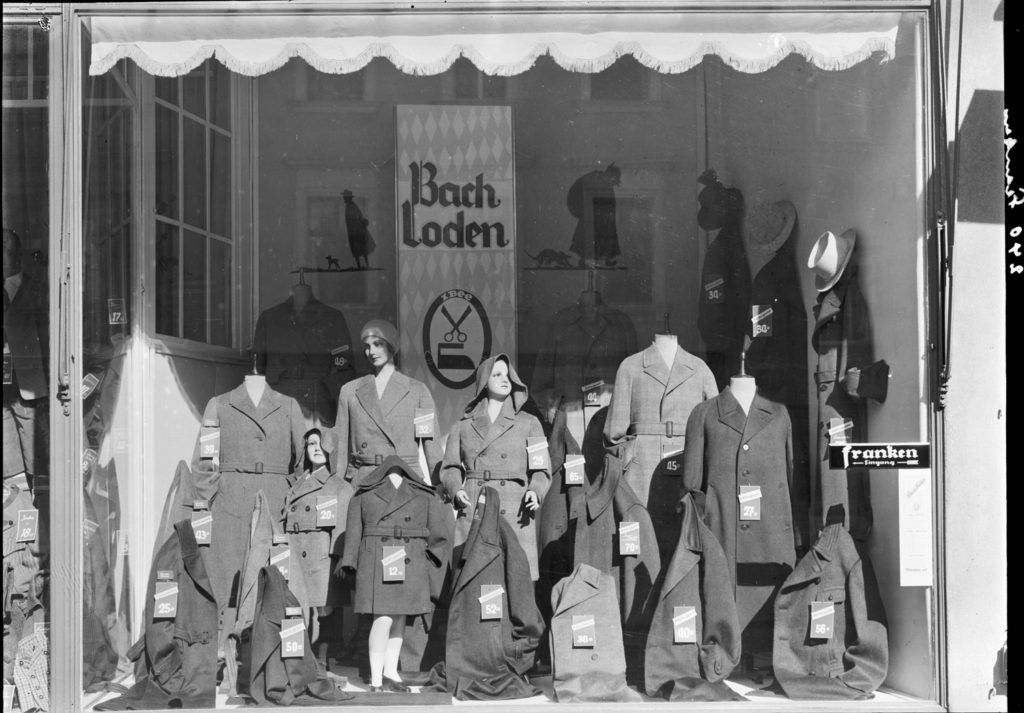

Max Franken ran a men’s clothes shop in Ludwigstraße 36 in Hof, which he registered on 2nd March 1914. In 1919 he also opened a textile wholesale business and in 1921 a tailor’s shop with workshops in Klosterstraße 10 and 27 as well as Ludwigstraße 36 and 39. His daughter Käthe reported that the family was among the most respected businesspeople in northern Upper Franconia. Since the number of employees and the turnover were very high, the company was even acknowledged as a factory.

The family had a nanny and a laundress but Therese Franken did the cooking herself and also helped in the business. The business went well until the agitation against the Jews continued to increase. Max Franken, who was called the “father of the poor and needy” because of his charity and helpfulness, wrote to the city council of Hof in 1920 about his concerns caused by the increasing antisemitic agitation.

For Max Franken, the “German Day” on 16th September 1923, when Hitler visited Hof, was already the “first nail on the coffin” of his company. People began to avoid Jewish businesses. Nevertheless, he succeeded in expanding his business in the following years. After the National Socialists had come to power he had to accept massive losses. During the boycott of Jewish shops on 1st April 1933 he was arrested and two SA-men blocked the entrance to his shop. In 1936 his business came to a standstill.

In 1938 the Franken family had to move to Leipzig – into the apartment of a family of Polish Jews who had just been deported. For most Jews the marking with the yellow stars from 1941 onwards felt like a great humiliation. For Max Franken it was like a slap in the face from which he never fully recovered.

In 1941 Max Franken was ordered to leave the country by the Gestapo. At the end of August he was taken into custody because of being accused of omitting the ‘Israel’ suffix from company correspondence which had been imposed by the National Socialists. In prison he was brutally abused.

Organising the emigration imposed by the Gestapo involved many hurdles. However, by the time a transport from Berlin to Argentina opened up in September 1941, a new rule was valid that only allowed Jews over the age of 60 to emigrate. Max Franken finally had to leave for Buenos Aires alone at the age of 60 (his wife was only 56 years old). For him this time was one of the saddest and loneliest times of his life, also because he always lived with the uncertainty of how his daughters and his wife were doing.

Therese and the daughters were deported to the ghetto of Riga in January 1942, and in autumn 1943 to the Stutthof concentration camp. There, Therese Franken died on 11th December 1944 as a result of dysentery. His daughter Lore didn’t survive either. She died in April 1945 after the liberation by the Red Army due to the consequences of the exertions of the camp onher health. Margarete and Käthe survived the war, the deportation to the ghetto in Riga and the concentration camp Stutthof.

“Once again I would like to see the Meistersingers from Nuremberg on the festival hill in Bayreuth… once again experience a trip on a Rhine steamer from Rüdesheim to Bonn”, wrote 76-year-old Max Franken to an office in Hildesheim. He was not granted that wish. He died of a heart attack in his appartment in Buenos Aires on 2 May 1957.